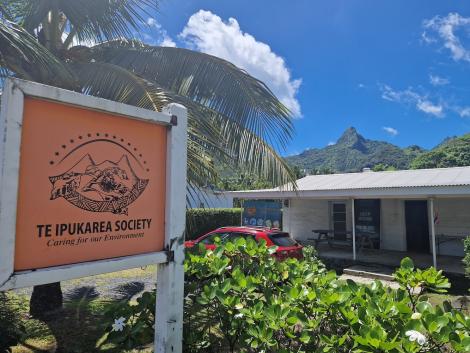

Thanks to funding from the National Science Centre, Poland, our PI participated in a research trip to New Zealand and the Cook Islands earlier this year. He had the opportunity to exchange thoughts with several local actors and stakeholders.

Could the approach of Māori communities be successfully applied to international and European challenges? How much of the RON-focused discourse is interwoven with specific cultural and ecological discussions? What can we learn from one of the few jurisdictions in which Rights of Nature seem to play a prominent role on the national level? These are but a few questions which could not be answered from the comfort of a European armchair, without an in-depth knowledge of the local context. From the beginning of the research project, we were certain that some part of the research needs to take place where Rights of Nature are either functioning or are actively discussed.

Unlike in Europe, where much of the debate is focused on optimal solutions for environmental protection, Rights of Nature in Aotearoa seem to be focused more on protection of the unique cultural and spiritual relationship between the Māori communities and the natural environment. Rights of Nature reflect the way in which local tribes (iwi) perceive and value the natural environment, This is why the emergence of RON-based frameworks is much more prominent on the North Island, which historically has been more densely populated by the Māori people thanks to a warmer, milder climate in the North. The lower numbers of indigenous inhabitants meant also that the postcolonial settlement processes in the South Island have largely been finalised before popularisation of the Rights of Nature approach.

From the perspective of the legal system, the RON-based approach is actually a fairly new one, as it emerged around 2009 as a response to the need of finding a new legal status for the Whanganui river, an entity with an immense cultural importance. This is not to say that such personification was a new thing – personified elements of nature have played a crucial role in Māori cosmologies. References to law are also coherent with the traditional way of thinking, according to which ecosystems were even described as legal systems (e.g. Te Awa Tupua, the ecosystem of Whanganui, was referred to as an ancient natural law system).

Development of RON in New Zealand was a result of efforts initiated with the aim to protect particular elements of nature. Whenever historical and cultural arguments come into play, it is much easier to demonstrate the social importance of a given ecosystem. This may be one of the reasons why the status of a legal entity was accorded to the Te Urewera forest and the Whanganui river, and the more general Fauna and Flora Claim has not been successful.

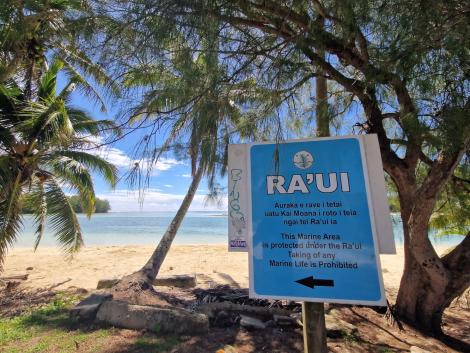

Even though the symbolic aspects of RON are clearly visible, Māori concerns are obviously not limited to protection of their cultural heritage and include also an emphasis on natural protection. The convergence of these two areas of interest is visible e.g. in the case of the Waikoropupū Springs, protected for a variety of reasons, including the purely environmental ones.

It seems that the primary consequences of RON were not environmental ones in the sense that they did not introduce a stricter regime of protection than in the case of national parks and other more standard modes of protection. That notwithstanding, it seems that RON did have an impact on reality. The iwi can now entertain a higher degree of inclusivity and independence when it comes to environmental management, what in some cases translates into reduction of environmentally detrimental practices such as excessive tourism or helicopter hunting.

Some challenges observed in the context of the research were related on one hand to the complex history of the region (including the sociopolitical differences between the situation of the Māori and Aboriginal people), and on the other to the often delicate political matter of negotiations and settlements (such as the ongoing negotiations about the legal status of Taranaki, which discourage the local experts from providing commentary on Rights of Nature).

The trip was a very interesting source of input on the abovementioned issues, as well as many more, such as inclusion of folk wisdom, traditional practices, and community leaders in decisionmaking processes. The outcomes are now being analysed and will consitute a valuable starting point for further research.